You might have creative aerobic deficiency syndrome

If you like to go at race pace all the time, this is the newsletter for you.

Before we begin, a quick note. Thank you for being a reader. I like to tell stories and connect ideas, and that means that my newsletters aren’t quick-hit tips and tricks. A couple of posts went viral on Hacker News, and I received angry comments from people that just wanted to know what the “Oxford writing tip” was. If I wanted to say something quickly, I’d tweet it, and I often do! Anyway, those are not my people. You are. Thank you for joining me here where it’s always an adventure in the #vanlife of podcast publications.

Today, a story about creative and athletic pacing.

Going all-out

On a cold morning in January of 1993, the angry tone of the alarm matched my mood. I dragged myself out of bed before the sun was up and took six gulps of orange juice straight from the carton to try and ease my sleep-deprived stomach. Hopping in my gray, ice-coated, hatchback ‘87 Toyota, I sped off into the blizzard to go to high school swim practice. In the dark, listening to “Head Like a Hole” by Nine Inch Nails, pouting, I drove toward the dingiest, oldest high school pool in Colorado Springs.

When I arrived, Mark Friedberg was already in the pool finishing his warm up—already going faster than I possibly could. With a Cheshire grin, he asked if I was going to go “all-out” today. “I don’t even want to get in let alone go fast,” I said. He coached me with some condescension that practice would only get easier if I went all-out all the time. “All-out,” I thought. He must know since he’s so much faster. And I have held that single thought about exercising ever since. Over twenty years of believing that if it’s not all-out, it’s not helping.

So, as we watch the Olympics, are we watching a bunch of people that have dedicated their lives to going all-out every time they jump in the water or lace on shoes? I’ve always assumed that we are.

But this thought has been frustrating. So much of my non-Olympian life I’ve noticed that people much faster than me didn’t seem to be suffering like me. I would bury myself trying to keep up with them while they would remain chipper and talk about what a beautiful morning it is. FUuuuckkk youuuuuu!

Eventually my swim career ended in burnout. I was over the pain, the early mornings, and the endless blue of the pool. I quit after my freshman year of college swimming. Years later, in fitful attempts to stay in shape, I’d try running. It always felt terrible. I would immediately get out of breath. Even the slowest jog spiked my heart rate. My legs burned and I gasped for breath training for 10Ks and longer races. And, I never performed well. My favorite part of running season was the end of it.

More recently I’ve been doing the same thing on a mountain bike around Eagle, Colo. I use Strava, and I fell into a cycle of going for personal best times (PRs) on almost every ride. All-out every time—feeling the burn. Over the last couple of years, I started to hear murmurings from some of my athlete friends that some low heart rate training was important, so maybe one in 10 rides, when I felt like absolute dogshit at the start, I would slow down.

Then I saw a tweet from one of my favorite, always informative tweeters, Paul Kedrosky. He was going on about something that sounded fascinating. What is aerobic deficiency syndrome (ADS)?

Going all-out creatively

Before we get into ADS, let’s talk about podcasting. I’ve taken that the same all-out all the time mentality that I’ve had in fitness into my creative pursuits including podcasting. In February 2018, when Chris and I left the high tables of the Denver Central Market, overcaffeinated and excited for a new podcasting adventure, the main thing on my mind was not—as it should have been—how we were going to make a great show. I was focused on when we could get the first episode “out the door.” We were on a footrace to publication.

Charitably, we probably believed we were going to get something out there and then go through cycles of feedback and improvement.

But, guess what? After going all-out as fast as we could and slopping something out, and after making the common mistake of setting ourselves on a weekly schedule, we had no room in the process for feedback and improvement. It was all we could do to keep up with the frantic publication pace we made for ourselves. We didn’t have any real feedback from anyone because that’s not how podcasting works.

So now we were stuck with a bad show that we made hastily, on an unsustainable schedule with no planned breaks. Our creative muscles couldn’t keep up with the turnover and were starved for oxygen. We were doing the podcasting equivalent of going all-out in every workout. We had tried to take a shortcut to greatness and ended up topping out at upper-mediocre. This has got to resonate with a few people.

The importance of training your aerobic base

Remember, I was wondering what aerobic deficiency syndrome is. It’s what happens to people that only ever go all-out all the time. Apparently your muscles cells need specific training to be able to produce ATP (energy) from stored fat. If they get this training they can propel you extremely fast on nothing but the intramuscular fat in your body for hours on end and your muscles don’t produce any lactic acid (pain) so the whole experience is quite comfortable.

If they don’t get this training because you always go all-out, then your muscles only learn how to make ATP from stored glycogen (sugar) which results in the production of lactic acid (pain), requires higher heart rates, faster breathing, and feels bad—even when you’re going fairly slowly.

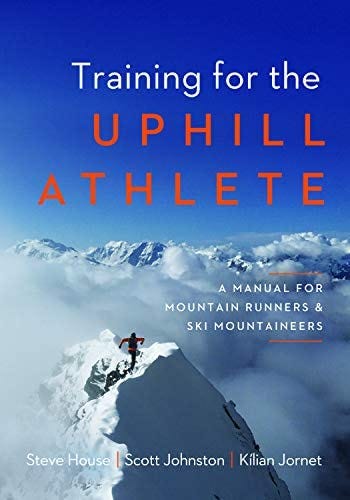

I learned all about ADS and how to overcome it from the book Training for the Uphill Athlete by Kílian Jornet Burgada, Scott Johnston, and Steve House. Its early pages were a revelation, and they spoke my language:

Don’t believe that there is a newly discovered shortcut to endurance fitness that only these overhyped fitness fads have discovered. If that were true, professional endurance athletes of all stripes would be beating down the doors of their local CrossFit.

To overcome ADS, you have to slow down. You have to be willing to run slowly, sometimes walk, for hours and hours until your cells learn how to make energy from fat, then slowly but surely you can start to move faster.

The bigger revelation for me is that athletes in endurance sports from running, to Nordic skiing, to swimming spend significantly more of their time (75-90% of total time) going relatively easy at low heart rates than they do going all-out. This is true for the entirety of their careers.

So we don’t need to feel bad for elite athletes out there suffering with burning legs day after day. They are spending almost all their time going at a pace that feels comfortable and pleasant—intoxicating even.

The only ones who hate long, slow aerobic capacity–building runs and skis are those who have never known what it feels like to sail up the mountain, nose to the wind, with ease. Relaxed, poised, moving fast and flying.

Training your creative base

Just as there isn’t a shortcut to endurance in fitness, there are no shortcuts to making a great show.

Great shows can only be made by people willing to put in the hard work. Feedback is the creative oxygen that your brain needs to rely on, and you need to seek it out and incorporate it into your creative products.

To keep with the analogy, you need to build your creative base before you go all-out. This means getting early feedback on your ideation, your show structure, your host plans, your season arc, and some episode outlines. Feedback at these early stages requires a willingness to go slow and be patient—not just get something out the door.

Have you noticed that when you listen to some of your favorite shows, the hosts talk about how certain episodes were months or even years in the making? They were going slow, doing all the research, letting the story reveal itself. They were working within their “aerobic capacity.”

What about those creative people that are super prolific and seem to generate more minutes of quality creative output than their peers? With our analogy, these are the people that have built up a high aerobic threshold.

High creative output people might be able to have several different projects moving along at a sustainable pace at the same time. Each of these projects is not being rushed, but these creators produce so much because they’re stewarding multiple things through the creative pipeline at once. And, like Mark Friedberg, they might Cheshire cat grin while they tell you, falsely, that they are always running at full-tilt.

This is not to say you should go start five podcasts, but you might notice that you have some downtime waiting for people as you’re working on one show, and eventually you might feel like you’ve caught your breath enough to start something new during that downtime.

I hope this analogy was as fun for you to read as it has been for me to think about for the past several weeks and months. There are very few books that I’ve read in my life that have initiated paradigm shifts that bleed into every facet of the way I operate and think about the world. This is one of them.

I lived this because I changed the way I exercise in January of this year, I saw my body transform into a fat burning exercise machine and melt away 25 pounds. I trained for a triathlon with a goal to break two hours, and I finished it in one hour and 47 minutes. While arriving to one of the transition zones in first place overall I heard someone who has known me for years say, “Christensen!? What?!”

As always, I’d like to invite you to join The Edit. We’ll provide you some creative oxygen. We had a few new people join this week. Some of the people we’re reviewing already have successful shows, and it’s an incredible honor that they’re interested to hear what we have to say.

Here’s the link to join: https://timber.fm/the-edit/

See you next week!

—Jon Christensen